When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, the need for accurate data to understand the nature of the pandemic, to respond and to quickly assess the impact of the response became very clear. The public health agencies at the local, state and federal levels started to contact providers for additional data beyond what was already being made available through established reporting mechanisms, including:

- Case reporting—In the absence of widely adopted electronic case reporting, jurisdictions started to ask for HL7®, Clinical Data Architecture (CDA®), and Consolidated CDA Continuity of Care Documents using available channels or rapidly deployed new channels including HIEs, direct messaging, and national networks. Additionally, electronic laboratory reporting transactions were expanded to fill gaps.

- Operational reporting—Operational statistics on tests, equipment, supplies, and patient statistics by setting, treatment and disease state became important to manage focus, logistics and policies to slow infections, hospitalizations and deaths. Much of the reporting required manual processes since an automated reporting infrastructure did not exist.

- Research—Requests from outside the public health agencies for access to real-world data increased dramatically to augment public health and gain early, exploratory insights into the nature of the pandemic and impact of early treatment alternatives beyond basic case reporting.

- Immunization reporting—While immunization reporting had the benefit of an already widely adopted reporting and data sharing infrastructure, additional data was still needed to understand distribution patterns across priority groups and in some jurisdictions the use of other medications as well. Furthermore, supporting mass vaccination sites created not only challenges on how to schedule and manage vaccinations, but also on documentation and reporting vaccinations in settings that did not have the necessary healthcare information technology. Accessing a patient’s full vaccine record across jurisdictions became more critical and further highlighted the absence of unique patient identifiers to match distributed records across providers and jurisdictions.

Across these areas we identified several common themes:

- Reporting and submission requirements for content, format and submission frequency varied across jurisdictions at local, state and federal levels, amplifying the challenge to rapidly roll out new and enhanced reporting capabilities.

- Communication and coordination of data requirements were challenging at best. As public health and research entities—among others—made requests, it was a challenge to understand where to go for clarifications and guidance, how to align across technology vendors and other key stakeholders such as public health jurisdictions, and what new requirements could be expected next. There was no established infrastructure for lines of communication where one knew where to go for information and guidance, or which organizations to involve early and frequently to solve problems and roll out a new reporting requirement. Ownership and contact information were unclear and/or lacking across all stakeholders.

- Consent requirements varied by jurisdiction and data sets of interest, particularly between who was making the requests: public health vs. research entities. Also, the public health emergency declarations and Health and Human Services (HHS) clarifications added complexity.

- Electronic case reporting adoption was insufficient to support time-critical data.

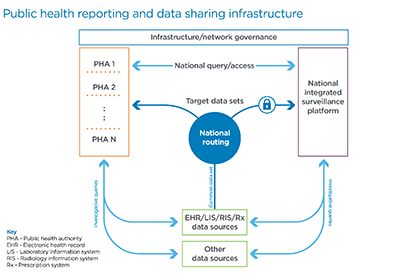

There is consensus across the industry that the U.S. needs to substantially enhance the public health reporting and data sharing infrastructure to not only be prepared for the next emergency, but also to improve its ongoing efficiency and effectiveness.

Source: Cerner

These challenges are addressable. Using the above framework we used to visualize the key areas of focus from the discussions in progress, we suggest the following initiatives be vigorously pursued in the context of a national public health reporting infrastructure framework, of which many elements are already being discussed across the various stakeholder communities.

- A common data set for ongoing submissions for specific reporting requirements where data is focused on the purpose at hand, particularly: syndromic surveillance reporting, laboratory results reporting, electronic case reporting, immunization reporting, other clinical/public registry reporting, electronic vital records reporting, trauma and injury reporting, and operational surveillance reporting.

- National, consistent routing where a provider can submit once and all relevant parties receive their applicable, targeted data set, whether identifiable or de-identified.

- A national, integrated surveillance platform that encompasses the variety of current systems deployed across HHS (e.g., National Healthcare Safety Network, National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System, Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, etc.)

- State-level, integrated surveillance platforms that serve the public health authorities within each state.

- Enabled bi-directional, national queries with access across all levels of jurisdiction based on the authority of the data requester, e.g., provider, consumer, local, state, or federal agency.

- Investigative queries into the original source or other sources for data not included in the ongoing, steady or normal state reporting.

This must occur within an infrastructure and governance framework for trusted access and exchange with the ability to pull a complete patient record (identified or de-identified as appropriate) for the right, authorized audience. This framework should incorporate the following:

- Governance must cover all jurisdictions—local, state and federal, plus infrastructure stakeholders, particularly providers and the health information and technology suppliers and networks.

- A common trust framework is needed to eliminate point-to-point data sharing agreements while easing rapid scaling and expansion and shifting access patterns (e.g., patient re-locations in case of emergencies).

- Absent a common, unique patient identifier, there must be a clear patient identity and matching approach enabling a patient’s record to be fully assembled (identifiable or de-identified) for both overall population health management and emergency management.

- All data exchange and access must be standards-based with minimum variations across jurisdictions in terms of transport, syntax and semantics, while recognizing the varied needs for the applicable data sets (e.g., identified vs. de-identified, more or less reportable conditions or tests, more or less data).

- A proactive emergency preparedness plan with training is needed to raise overall preparedness, including alternative network connectivity and offline access, as well as the ability to access and share incremental data for emergencies. This should encompass alignment with exploratory research initiatives that augment the public health response.

- Increased and optimized funding is needed for the infrastructure and supporting workforce to expand the essential capabilities to implement, manage and evolve a modernized public health infrastructure that supports all local, state and federal requirements.

As the industry works together across providers, jurisdictions, agencies, health IT suppliers and other industry experts to make improvements in all the areas identified above, there are four topics that should rise to the top of conversations.

1. Patient Identification and Matching

A clear and complete perspective of an individual and a population is essential, requiring patient records to be associated with the right patient within and across jurisdictions, where identifiable data is permissible and authorized. We cannot overemphasize the importance of a continued focus to improve in this area. A collaborative approach between public health jurisdictions and national networks, directly or through state HIEs, presents the opportunity to substantially improve on our current state that both benefits normal operations and emergency operations.

2. Universal Adoption of Electronic Case Reporting

At the start of the pandemic, standards-based electronic case reporting (eCR) was minimally deployed. Progress has been made to expand and further enable rapid expansion of electronic case reporting. Considering this capability as the cornerstone, and its absence as one of the biggest challenges to get access to the necessary data fast, it is imperative that we push hard to get this deployed nationally as rapidly as possible.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) took the step to kick-start an open source, HL7® FHIR®-based Substitutable Medical Apps, Reusable Technology (SMART) application that can plug into the emerging FHIR-based application programming interface (API) capabilities. Health information and technology, thus EHRs, should support this to become certified against the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology’s Certification Edition Cures Update, providing three key benefits:

- Over the next one to two years, certified software will roll out that supports the necessary FHIR-based APIs plus SMART framework, enabling rapid deployment of the eCR Now FHIR app app.

- The eCR Now app will generate a case report using HL7’s Electronic Initial Case Report standard, thus further driving alignment across public health jurisdictions.

- The architecture enables more rapid adjustments to new reportable conditions and data as the need emerges, reducing (if not eliminating) the need to impact workflow-focused data flows such as electronic laboratory reporting and immunization reporting for incremental data needs beyond what is relevant to that workflow.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ proposed required support for four of the public health reporting flows as part of the Promoting Interoperability program, syndromic surveillance, electronic laboratory reporting, electronic case reporting, and immunization reporting and queries. This must be implemented.

3. Common Report Routing Infrastructure and Standards

The current report submission and routing approach includes many point-to-point connections and submitting the same or similar report to multiple jurisdictions. This should be replaced with a routing framework where one nationally agreed upon data set for defined use case sets can be extracted and adjusted to a jurisdiction’s specific subset and patient de-identification requirements. This would advance the models currently deployed eCR through messaging services and for syndromic surveillance through the CDC’s National Syndromic Surveillance Program’s Electronic Surveillance System for the Early Notification of Community-Based Epidemics.

4. Queries

Although much focus is on the reporting and data collection (whether pushed or pulled) enabling queries for data across various data repositories is critical. Such queries include:

- Queries to pull a patient’s record together across those sources

- Queries for incremental data where regularly submitted data is not enough and may need to reach back in time

- Queries for insights into and dashboards of aggregated data of one’s surrounding area and nationwide

Our public health reporting and data sharing infrastructure has gaps that must and can be filled. Together we can make that happen by staying connected and building on the experiences gained over the last year and a half. Let’s keep that momentum going and accelerate the pace.

Sponsored content. The views and opinions expressed in this content or by commenters are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of HIMSS or its affiliates.